[ad_1]

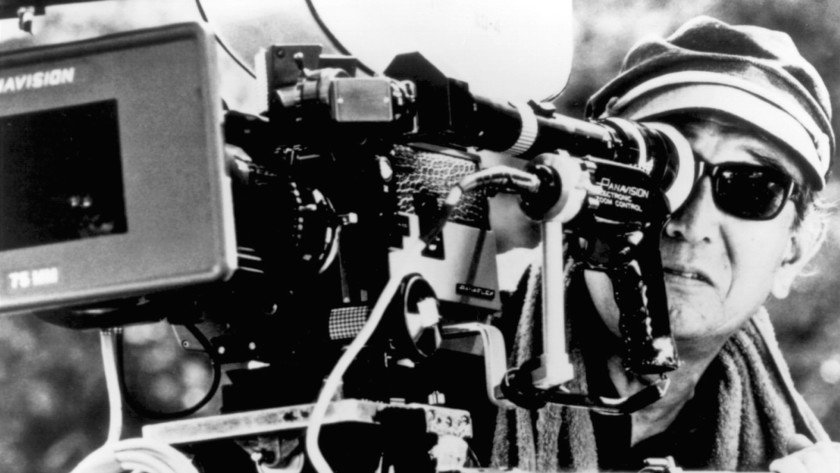

For my generation, you cannot talk about Japanese films without mentioning Kurosawa Akira and the awesome films he produced and directed. I have been watching Kurosawa films for most of my adult life and I agree he was a very influential director. Many of the U.S. westerns borrowed plot lines and visuals from him. Star Wars was hugely influenced by Kurosawa’s techniques and storytelling.

Most great artists have tortured souls and Kurosawa was no exception. I will try my best to summarize his awesome life in this fan guide but please make sure to check out my sources that go into a lot more detail than what I can do in this small space.

Name: Kurosawa Akira

Kanji Name(s): 黒澤明 or 黒沢明 or 黑澤明

Hiragana Name:くろさわ あきら

| Birth: March 23, 1910 (Meiji 43) Death: September 6, 1998 (Heisei 10) Jobs: Director and Screenwriter |

|

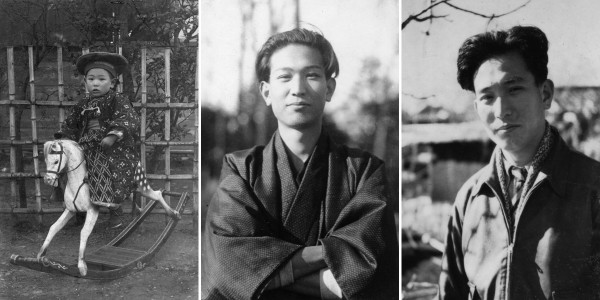

Image: Akira Kurosawa at age three, in his early 20s, and his late 20s

Image: Akira Kurosawa at age three, in his early 20s, and his late 20s

Childhood

Akira Kurosawa was born on the 23rd of March 1910 (Meiji 43) in Oimachi in the Omori district of Tokyo. His father Isamu Kurosawa, from a Samurai clan in Akita, worked as the director of the Army’s Physical Education Institute’s lower secondary school, while his mother Shima came from a merchant family living in Osaka. Akira was the eighth and youngest child of the moderately wealthy family, with the oldest two already grown up and one has died, leaving Kurosawa to grow up with three sisters and one brother.

Akira’s father promoted exercise, so Akira was the captain of his school’s kendo club. Isamu was open to western traditions and saw theatre and motion pictures as educationally valuable, encouraging his children to watch films. Another strong influence on young Akira was his elementary school teacher Mr. Tachikawa, whose progressive educational practices ignited in his young pupil first his love of drawing and then an interest in education in general. This is also when he learned calligraphy.

Another major childhood influence was Heigo Kurosawa, Akira’s older brother by four years. In the aftermath of the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923, which devastated Tokyo, Heigo took the 13-year-old Akira to view the devastation. When the younger brother wanted to look away from the human corpses and animal carcasses scattered everywhere, Heigo forbade him to do so, encouraging Akira instead to face his fears by confronting them directly. Some commentators have suggested that this incident would influence Kurosawa’s later artistic career, as the director was seldom hesitant to confront unpleasant truths in his work. (wikipedia)

He later moved in with his older brother, who had failed the exams to get into one of Tokyo’s top schools. Akira had dreams to become a painter, but could not sell any of his paintings, got discouraged and gave up his pursuit of that career path. Heigo was a silent film narrator (Benshi) at the time and was starting to make a name for himself and the two were inseparable. In the 1930s when talking movies came out and Heigo began to lose work, Akira moved back home and, in 1933, Heigo committed suicide and his eldest brother died within a span of four months, leaving Akira the only brother with 3 surviving sisters.

During production of The Most Beautiful, the actress playing the leader of the factory workers, Yaguchi Yoko, was chosen by her colleagues to present their demands to the director. She and Kurosawa were constantly at loggerheads, and it was through these arguments that the two, paradoxically, became close. They married on May 21, 1945, with Yaguchi two months pregnant (she never resumed her acting career), and the couple would remain together until her death in 1985. They had two children, both surviving Kurosawa as of 2018: a son, Hisao, born December 20, 1945, who served as producer on some of his father’s last projects, and Kazuko, a daughter, born April 29, 1954, who became a costume designer. (Wikipedia)

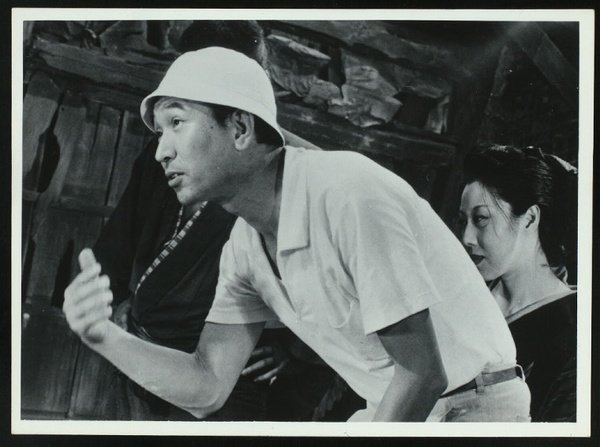

Directing

In 1935 Kurosawa answered an ad in the paper for Photo Chemical Laboratories (PCL), which would later become Japan’s leading studio – Toho – advertising that they were looking for new assistant directors. While Akira had no strong interest in the film industry, he still filled out the essay on the deficiencies of Japanese films. His half-mocking essay earned him a callback, and while his results were not on par with the other second-rounders, one director Yamamoto Kajiro was intrigued. In February 1936, Kurosawa started working for PCL. Most of us are familiar with the movies he directed so I will only list below the movies where he had a different Job.

THIRD ASSISTANT DIRECTOR

CHIEF ASSISTANT DIRECTOR

He received a promotion after Enoken’s Kinta Part 2 and the following movies he gets the billing of Chief assistant Director

Most of the pre-war movies have been lost and we cannot view them today, but their existence is proven in logs and record books.

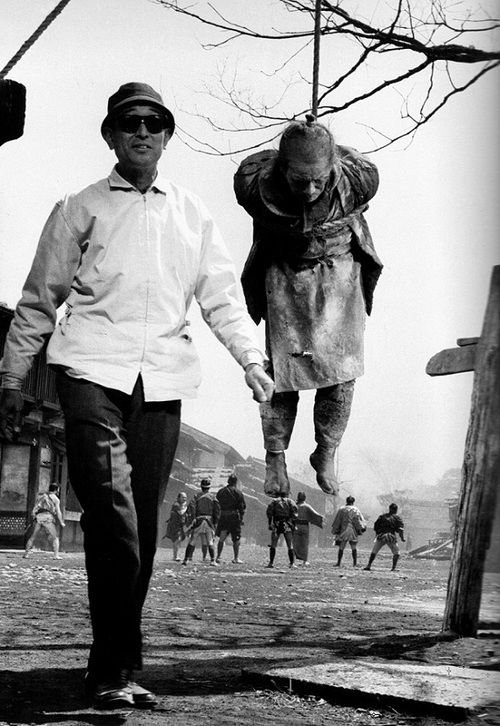

In 1943, Kurosawa was promoted to director and he had his directorial debut with Sanshiro Sugata. The film is based on the novel by the same name by author Tomita Tsueno. The film follows a man named Sanshiro who travels to the city to learn jujitsu. Whilst there, he witnesses a man doing a different form of self-defense – judo – and begins to focus on it.

The film is seen as an early example of Kurosawa’s immediate grasp of the film-making process, and includes many of his directorial trademarks, such as the use of wipes, weather patterns as reflections of character moods, and abruptly changing camera speeds. [Wikipedia]

The film became influential at the time of release and has been remade five times over the course of the years. Kurosawa also went on to direct a sequel, Sanshiro Sugata Part II.

Besides being a director he was a screenwriter, producer, editor, and even song lyricist involving himself in many of the processes of filmmaking. During his early directing days he did not make enough money to support his new family so he supplemented his income by doing screenplays. Dohyo Matsuri and The Admirable Ishin Tasuke are two of his earliest ones after the war. During the Toho dispute, he left Toho and created another production company to be contacted by other film companies. The Film Art Association (Eiga Geijutsu Kyōkai) was formed in 1948 with producer Motoroki Sojiro, and fellow directors Yamamoto Kajiro, Naruse Mikio, and Taniguchi Senkichi. By 1952 and the filming of Ikiru he is back with Toho studios, this time with international fame from Rashomon. His films became bigger productions that became more and more costly so Toho executives convinced him to bank role with some of his own money going in 50-50 with Toho. This was the beginning of “Kurosawa Production” of which Toho was the biggest shareholder on April 1st, 1959 whose offices were at Toho headquarters. After the Tora!Tora!Tora! dispute Kurosawa would never work with Mifune or screenwriter Kikushima Ryuzo ever again. Kurosawa Production had a top officer resign and it was a dark time for Kurosawa. His friends, Kobayashi Masaki, Kinoshita Keisuke, and Ichikawa Kon came together and put together yet another production company this time named “Yonki no Kai production” (Club of Four Knights) in July 1969.

During the Toho dispute, he left Toho and created another production company to be contacted by other film companies. The Film Art Association (Eiga Geijutsu Kyōkai) was formed in 1948 with producer Motoroki Sojiro, and fellow directors Yamamoto Kajiro, Naruse Mikio, and Taniguchi Senkichi. By 1952 and the filming of Ikiru he is back with Toho studios, this time with international fame from Rashomon. His films became bigger productions that became more and more costly so Toho executives convinced him to bank role with some of his own money going in 50-50 with Toho. This was the beginning of “Kurosawa Production” of which Toho was the biggest shareholder on April 1st, 1959 whose offices were at Toho headquarters. After the Tora!Tora!Tora! dispute Kurosawa would never work with Mifune or screenwriter Kikushima Ryuzo ever again. Kurosawa Production had a top officer resign and it was a dark time for Kurosawa. His friends, Kobayashi Masaki, Kinoshita Keisuke, and Ichikawa Kon came together and put together yet another production company this time named “Yonki no Kai production” (Club of Four Knights) in July 1969.

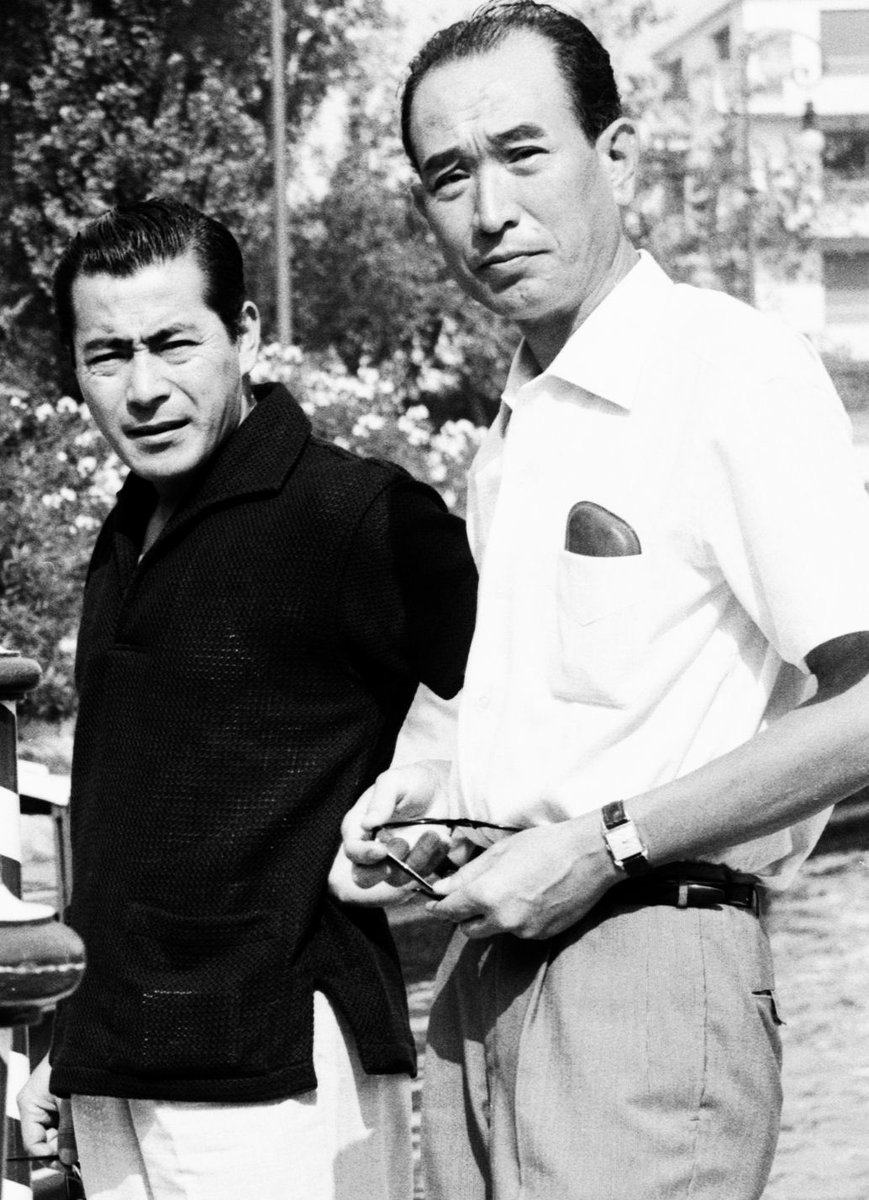

“All the films that I made with Mifune, without him, they would not exist.” – Akira Kurosawa

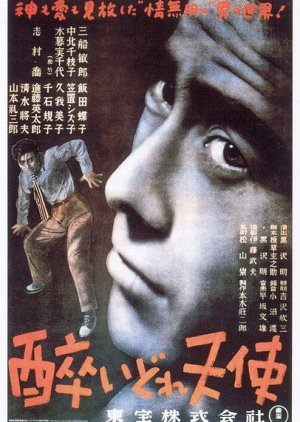

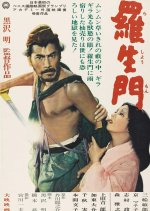

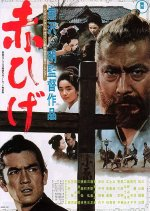

Chambara (sword fighting) – a subgenre of Jidaigeki (period or Era) – movies were banned for seven years by the Americans after the war. Mifune’s first movie with Kurosawa in 1948 was Drunken Angel, then Stray Dog 1949 and, when the ban was lifted, Kurosawa was ready in 1950 with Rashomon. Together, they went on to make 16 (IMDB List) movies together before parting ways after the fiasco with Red Beard.

During the time he was making Red Beard, Mifune could not take any other jobs because he was required to grow out an actual beard, and it hit him financially. So, as soon as it was finished, he took any job that came up and Kurosawa took this as defection. He stated he would never cast someone who was in a show like Shogun (1980) and cast a different lead when he was suggested for Ran.

Kurosawa presented Mifune with the Kawashita Award which he had won two years before. They finally made a move towards reconciliation in 1993 at the funeral of their friend Ishiro Honda. After making eye contact, they tearfully embraced one another, ending nearly three decades of mutual avoidance.

Tora! Tora! Tora! and the beginning of the Kurosawa blue period.

Language barriers caused most of the issues that created this huge fiasco between Kurosawa Productions and 20th Century Fox. The Middle man, Tetsuro Aoyagi, negotiated everything and approved all the contracts. Kurosawa trusted him and he delivered the wrong information to both sides. Kurosawa believing he played a bigger role in the production of the movie than he actually did. Clashes over the script started almost day one.

In 2002, Tasogawa visited the 89-year-old Elmo Williams in Oregon. Williams, then retired, acknowledged that he had made a mistake in choosing Kurosawa, although the choice seemed excellent at the time because the senior American executives and Williams respected Kurosawa as a fellow movie maker. Williams liked Kurosawa as a sensitive man but felt that Kurosawa never opened his heart to him. He understood that Kurosawa’s explosive temper, which poisoned the working environment, reflected his acute anxiety and the pressure he felt to produce a great movie. Kurosawa once said “Tora! Tora! Tora!” would be a record of neither victory nor defeat but a record of mutual misunderstanding and miscalculation and the waste of excellent human capabilities and energy. Tasogawa’s account of the production of this movie is exactly that. – Japansociety UK

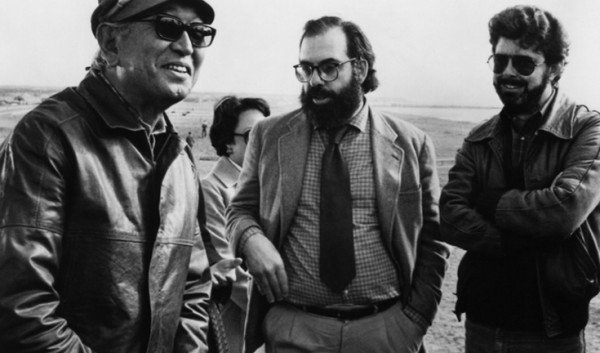

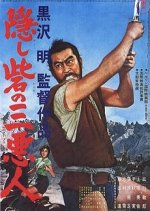

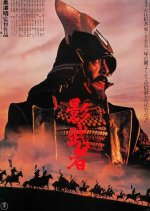

After this Kurosawa had trouble securing funding for his films, while he had released a few more films they did not reach the same success his previous works had done. A fan of his work would come to his rescue, George Lucas. Star Wars had borrowed elements from The Hidden Fortress and was a major success. Lucas used the sequel as leverage to get funding for Kurosawa’s Kagemusha. After much hardships and a delayed-release date, this would mark Kurosawa’s come back more than double the amount of money spent to produce it.

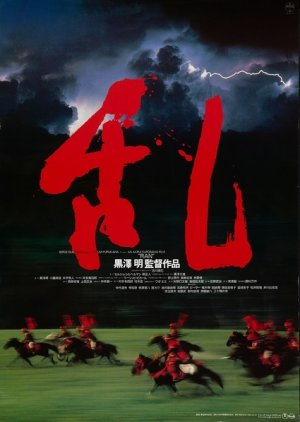

His next work was Ran, which did mediocre domestically but was a success abroad in Europe and America. His next project was Dreams. He wrote the script entirely himself and was based on his own dreams. His son, Hisao, who had helped with his last previous movies was in principal production, and his daughter, Kazuko worked in wardrobe. He still was having trouble getting funding from Japanese companies for this project so he once again turned to international investors and reached Steven Spielberg who saw value in the project.

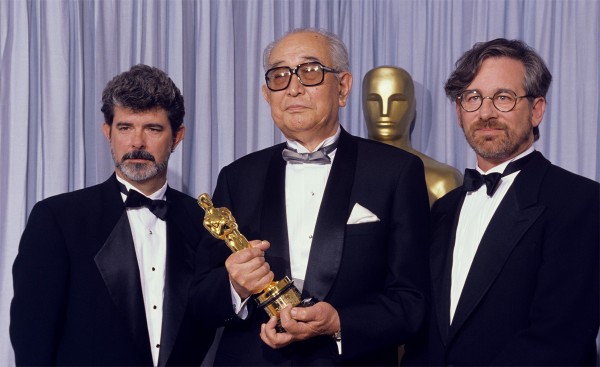

Kurosawa, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg at the 1990 Academy Awards

Madadayo was his last directed film because in 1995 he slipped t home and injured his spine. This injury caused him to be confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his days. In 1998, after many years of his body slowly failing, he passed away of a stroke.

Awards

The original chart is taken from Wikipedia and modified

| Year of Award or Honor (if known) |

Name of Award or Honor | Awarding Organization (if known) |

Country of Origin |

Given for… | Film Title (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1943 | Sadao Yamanaka Prize | (NK) | Japan | Film | |

| The National Incentive Film Prize [Shared with Torii Kyouemon] |

(NK) | Japan | Film | ||

| 1948 | Mainichi Film Concours | Mainichi Shimbun (newspaper) |

Japan | Directing |  One Wonderful Sunday One Wonderful Sunday (1947) |

| 1949 | Kinema Jumpo Award (Critics’ Award) |

Kinema Jumpo magazine | Japan | Film |  Drunken Angel (1948) Drunken Angel (1948) |

| Mainichi Film Concours | Mainichi Shimbun | Japan | Film | ||

| (NK) | Geijutsusai (Arts Festival) Grand Prize |

Ministry of Education | Japan | Film |  Stray Dog (1949) Stray Dog (1949) |

| 1951 | Blue Ribbon Award | The Association of Tokyo Film Journalists |

Japan | Screenplay (with Shinobu Hashimoto) |

Rashomon (1950) Rashomon (1950) |

| Golden Lion (First prize) |

Venice Film Festival | Italy | Film | ||

| NBR Award | National Board of Review | USA | Film, Directing |

||

| 1952 | Honorary Award – Outstanding Foreign Language Film |

AMPAS (Academy Award) |

USA | Film | |

| 1953 | Kinema Jumpo Award | Kinema Jumpo magazine | Japan | Film |  Ikiru (1952) Ikiru (1952) |

| Mainichi Film Concours | Mainichi Shimbun | Japan | Film, Screenplay (with Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni) |

||

| (NK) | Arts Festival | Ministry of Education | Japan | Film | |

| 1954 | Special Prize of the Senate of Berlin |

Berlin Film Festival | Germany | Film | |

| 1954 | Silver Lion of St. Mark (Second Prize) |

Venice Film Festival | Italy | Film |  Seven Samurai (1954) Seven Samurai (1954) |

| 1959 | Diploma of Merit | Jussi Award | Finland | Directing | |

| Blue Ribbon Award | The Association of Tokyo Film Journalists |

Japan | Film |  The Hidden Fortress (1958) The Hidden Fortress (1958) |

|

| Silver Berlin Bear | Berlin Film Festival | Germany | Directing | ||

| FIPRESCI Prize | The International Federation of Film Critics (Berlin Film Festival) |

Germany | Film | ||

| 1961 | Golden Laurel Award | David O. Selznick | USA | Film |  Ikiru (1952) Ikiru (1952) |

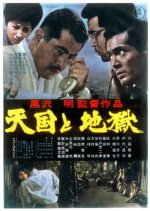

| 1964 | Mainichi Film Concours | Mainichi Shimbun | Japan | Film, Screenplay (with Ryuzo Kikushima, Eijiro Hisaita and Hideo Oguni) |

High and Low (1963) High and Low (1963) |

| Golden Laurel Award | David O. Selznick | USA | Film | ||

| 1965 | Asahi Culture Prize | Asahi Shimbun | Japan | Film |  Red Beard (1965) Red Beard (1965) |

| Foreign Honorary Member | American Academy of Arts and Sciences | USA | Career | ||

| Journalism, Literature and Creative Communication Arts | Ramon Magsaysay Award | Philippines | Career | ||

| OCIC Award | OCIC (later Signis) (Venice Film Festival) |

Italy | Directing |  Red Beard (1965) Red Beard (1965) |

|

| (NK) | Soviet Filmmakers’ Association Prize[4] |

Moscow Film Festival | USSR | Film | |

| (NK) | Million Pearl Award | Tokyo Roei | Japan | Film | |

| (NK) | NHK Award | NHK (broadcaster) | Japan | Film | |

| 1966 | Blue Ribbon Award | The Association of Tokyo Film Journalists |

Japan | Film | |

| Mainichi Film Concours | Mainichi Shimbun | Japan | Film | ||

| Kinema Jumpo Award | Kinema Jumpo magazine | Japan | Film Directing |

||

| (NK) | Geijutsusai (Arts Festival) Prize for Excellence |

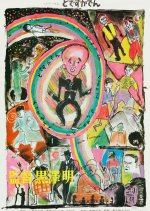

Ministry of Education | Japan | Film |  Dodesukaden Dodesukaden(aka, Dodeskaden) (1970) |

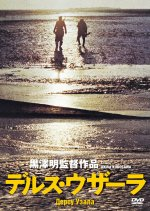

| 1975 | Golden Prize | 9th Moscow International Film Festival | USSR | Film |  Dersu Uzala (1975) Dersu Uzala (1975) |

| FIPRESCI Prize | The International Federation of Film Critics (Moscow Film Festival) |

USSR | Film |  Dersu Uzala (1975) Dersu Uzala (1975) |

|

| 1976 | Best Foreign Language Film | AMPAS (Academy Awards) |

USA | Film | |

| 1977 | David | David di Donatello Awards | Italy | Directing | |

| Silver Ribbon | Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists |

Italy | Film | ||

| 1978 | Prix Léon Moussinac | Syndicate of French Film Critics |

France | Film | |

| Golden Halo | Southern California Motion Picture Council |

USA | Film | ||

| 1979 | Honorary Prize | 11th Moscow International Film Festival | USSR | Career | – |

| 1980 | Palme d’Or (First Prize) |

Cannes Film Festival | France | Film |  Kagemusha (1980) Kagemusha (1980) |

| Hochi Film Award | Hochi Shimbun (newspaper) |

Japan | Film | ||

| 1981 | Blue Ribbon Award | The Association of Tokyo Film Journalists |

Japan | Film | |

| Mainichi Film Concours | Mainichi Shimbun | Japan | Film, Directing |

||

| Reader’s Choice Award | Mainichi Shimbun | Japan | Film | ||

| César | César Awards | France | Film | ||

| David | David di Donatello Awards | Italy | Directing | ||

| BAFTA Film Award | BAFTA | UK | Directing | ||

| Silver Ribbon | Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists |

Italy | Directing | ||

| 1982 | Career Golden Lion | Venice Film Festival | Italy | Career | – |

| 1985 | LAFCA Award | Los Angeles Film Critics Association |

USA | Film, Career |

Ran (1985) Ran (1985) |

| NBR Award | National Board of Review | USA | Film, Directing |

||

| OCIC Award | OCIC (later Signis) (San Sebastián Film Festival) |

Spain | Film | ||

| BSFC Award | Boston Society of Film Critics | USA | Film | ||

| NYFCC Award | New York Film Critics Circle | USA | Film | ||

| 1986 | NSFC Award | National Society of Film Critics | USA | Film | |

| Amanda Award | Norwegian International Film Festival | Norway | Film | ||

| Blue Ribbon Award | The Association of Tokyo Film Journalists |

Japan | Film | ||

| Bodil | Bodil Awards | Denmark | Film | ||

| David | David di Donatello Awards | Italy | Film | ||

| Mainichi Film Concours | Mainichi Shimbun | Japan | Film, Directing |

||

| Golden Jubilee Award | Directors Guild of America | USA | Career | – | |

| Akira Kurosawa Award | San Francisco International Film Festival |

USA | Career | – | |

| 1987 | BAFTA Film Award | BAFTA | UK | Film |  Ran (1985) Ran (1985) |

| ALFS Award | London Film Critics’ Circle | UK | Film, Directing |

||

| 1989 | Lifetime Achievement Award | AMPAS (Academy Awards) |

USA | Career | |

| 1990 | Special Prize | Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize | Japan | Career | |

| 1992 | theatre/film | Praemium Imperiale | Japan | Career | |

| 1992 | Lifetime Achievement Award | Directors Guild of America | USA | Career | |

| 1994 | Kyoto Prize in Arts and Philosophy | Inamori Foundation | Japan | Career | |

| 1998 | Special Award (for his work) (P) |

Nikkan Sports Film Award | Japan | Career | – |

| 1999 | Lifetime Achievement Award (P) | Awards of the Japanese Academy | Japan | Career | – |

| 1999 | Blue Ribbon Award Special Award (for his work) (P) |

The Association of Tokyo Film Journalists |

Japan | Career | – |

| 1999 | Mainichi Film Concours Special Award (for his work) (P) |

Mainichi Shimbun | Japan | Career | – |

| 1999 | Asian of the Century Award (Arts, Literature and Culture) (P) |

CNN AsianWeek (US) |

USA | Career | – |

| 2013 | Jean Renoir Award | U.S. Writer’s Association Award | USA |

This hugely influential director left his mark on the history of filmmaking forever. His ideas and styles are still visible in today’s movies, his stories are remade over and over again. I do not think this article does justice to his life so please be sure to check out my sources, some of which go into much more detail than I could go here.

Have you watched a Kurosawa film?

Which is your favorite?

What do you recommend?

Let me know in the comments.

Sources: Eng Wiki ~ IMDB ~ RottenTomatoes ~ Britannica ~ NYTimes ~ Biography ~ Wikiquote ~ Japanese Wikipedia ~ Eiga.com ~ Nicovideo ~ Akirakurosawa.info

Edited by: BrightestStar (1st editor), YW (2nd editor)

kurosawa akira

yamamoto kajiro

[ad_2]

Source link

More Stories

Park Hyung Sik and Han So Hee Radiate Chemistry in Cute Promotional Stills for Disney+ K-drama Soundtrack #1

Go Kyung Pyo in discussion to join Park Min Young and Kim Jae Young in a new drama

New Trailer is Out for “Green Mothers Club”